Transcript: Dr Tristan Casey:

Hi, I’m Dr. Tristan Casey from New View Safety. And today we’re talking about simple versus complex thinking, a special three part series where we can unpack some of the safety science essentials. So, let’s have a look at what we’ll be talking about today. So, in this module, you’ll learn about the differences between simple and complex thinking and how they shape the development of various safety management models. And by understanding these differences, you’ll be better equipped to categorize safety problems. So, figure out how to deal with them and apply the best strategy. So, grasping this notion of simple versus complex thinking is really critical to understand how different views of safety can be used together. What are we going to be learning? Well, there’s four key things as always. One, remember three different types of work systems and their characteristics. Two, understand the differences between simple and complex thinking. Three, apply these ideas and maybe have some conversations with other people in your organization about these different types of systems. And fourthly, evaluate which type of thinking you could use in different safety situations.

Let’s get into the content. So, let’s initially talk a little bit about the types of work systems that are possible. There’s simple, complex, and chaotic. So, a simple or ordered work system is one that behaves predictably and has a linear cause and effect relationship. So, when we say linear cause and effect, what we mean is that there’s a sequence or a trajectory of things that occur. Think about a ball rolling down a hill and striking another ball, or even a better example is probably a pool table. You strike the ball and then the other balls will be affected by that initial action, that’s a simple system. A complex system, most work systems are complex. This means that they cannot be reliably predicted and a non-linear. So, we mean here that simple starting points can lead to very complex unpredictable outcomes, and that’s the case with most organizations. They’re very complex interactive entities, I suppose.

And lastly, the chaotic work system, sometimes a work system will destabilize and it becomes what we call chaotic. This is a dangerous system state. And we’ll learn about each one of these types of systems and how to manage them from a safety lens. So, here’s some examples. So, a simple system is a production process that involves mainly mechanical components and problems are usually due to component failures. The complex system, a typical organization with people, technology, and processes all operating collectively. And lastly, the chaotic system is one where there’s a major disaster or loss of safety capability or safe or process safety, resulting in some sort of unpredictable situation. Our focus today is on the first two, simple and complex. So, let’s unpack that and look at it in more detail. So, simple systems are explained by what we call reductionist thinking, which basically means breaking down all of the pieces into its constituent parts.

Usually in a simple system, our focus is on fixing the symptoms rather than the deeper causes of trouble. So, simple systems seek to reduce and control variability to create order. And a key assumption is that outcomes are predictable if all starting conditions are known. So, in a nutshell, we’re saying that a simple system can be decomposed, it can be broken apart, we can understand the pieces and put them back together as we would with a basic production process. And the way we control them through safety techniques and management strategies is to constrain, control, reduce deviation or variability from the predicted norm. Some of the problems with simple safety systems, I guess, there are some problems we can actually deal with through this approach. When there is a safety problem that’s simple, our best strategy is to apply best practice, which is where there’s one clear, best way to do things or what we call good practice, where there’s multiple best ways, and we just need the help of experts to help us decide which one is possible.

So, simple safety problems are usually experienced at the coal face, the frontline, close to the actual work and involve just a few things or a few components. So example, when a required tools unavailable for the job, equipment fails or it malfunctions, or a procedure is not quite fit for purpose. In these situations, what the best strategy is to categorize the problem. Have we experienced this before? Have we got routines and strategies we can draw on or call in the help of experts to help develop a solution collaboratively? So, they’re our main tricks up our sleeves for simple safety problems. One of the most influential and well known simple safety model is the work of Heinrich. And many of you would be familiar with the accident triangle. This model suggests that safety incidents are the result of a cause and effect sequence, that sort a simple safety approach.

Distant factors like the social environment create context, in which the safety incident occurs. And the most proximal or immediate factors like unsafe acts and failures trigger the actual incident. I guess the corollary of this is that logically removing one or more of the dominoes stops the incident from occurring. The evolution of simple thinking, we go from the accident triangle through to Swiss cheese, and through to some models of safety culture, which might be surprising to you. But many of the what we call normative safety culture models are simple in nature. So, the accident triangle for the further work on Heinrich’s model resulted in this pyramid that suggested the predictive relationships amongst near misses, minor injuries, and fatalities. And the I guess, implication of that as if we stop the more frequent near misses, then we should avoid the fatalities.

And that’s been widely debunked, but can still be a useful heuristic for us to think about. Swiss cheese, James Reason’s model promotes a defenses in depth approach, whereby incidents can be arrested, we can stop them from happening. Although each layer is permeable, multiple defenses overcome the holes. And that’s the idea of the Swiss cheese, the holes are the lapses in our defenses or the weaknesses. And by having multiple layers of cheese, we can prevent things from going wrong. And lastly, safety culture. So as we said, most safety culture models are simple. There is an ideal or a template that the organization should try and replicate. In a good safety culture, in inverted commerce is said to stop injuries from happening. So, there’s some of the perils, some of the traps to watch out for. In terms of explanations, we are reductionist, which means that the system can be broken down and understood as pieces, which is not always the case. Cause and effect is explained through linear relationships, every action has a clear and predictable impact on the next factor or the next component, and that’s not always the case either.

Accountability, it really emphasizes individual accountability and even potentially blame it. It focuses on the sharp end of the organization or the work system. And variability, we must control and constrain to prevent things from deviating and going outside the boundaries of what we thinks acceptable. But in summary, simple safety models have their place. They’re useful tools to help explain work systems that are complicated, but not complex. They can be used to frontline to create simple defenses, but it might be inappropriate for activities that involve what we call social technical interactions in organizations. So, the combination of technologies and groups of people coming together, they’re not so helpful. But increasingly, we live in a volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous world that good old VUCA that you’re probably familiar with. And that means we cannot always be confident that the simple approach will be an appropriate one.

So, complex systems embraces what we call messiness. In a complex system, outcomes are unplanned and unexpected resulting from the interactions amongst the pieces in that system. Cause and effect relationships do not really make sense in this type of system. Instead, we look at patterns and trends. We take a macro overarching view of how things develop and evolve over time. Most types of safety problems are going to be complex. This is a place you should be comfortable dealing with. When this happens our best strategy is to experiment and bring diverse groups together to solve the problem through an emergent solution. So, there’s no real expertise that can be extracted here. There’s no best practice. It’s really about bringing a diversity of opinions to the situation. So, complex safety systems and problems are usually at the blunt end, away from the actual work and involve many different pieces.

For example, when the organization’s cultures, maybe impairing awareness and decision making, leadership’s ineffective, or introducing a new technology. So, in these situations, we probe, we experiment with fail safe ideas. We rapidly prototype and iterate and embrace the diversity of different views and perspective. Sorry, that’s our strategy. One of the most influential and well known safety models in this area is the work of Rasmussen. Rasmussen’s model suggests that work will migrate to an unsafe boundary due to pressures, financial and workload. The work system is best understood as a dynamic one and is constantly changing under different pressures and forces. So, logically our goal should be to understand and manipulate these forces that shape the work, rather than intervene in the work directly. So, we’re looking sort of outside of the context of what makes sense to the person and how that shapes their activities. So, a few different evolutions here, Rasmussen’s model, high reliability, organizing, and resilience engineering, that the progression of ideas.

So, Rasmussen’s model is a really key critical development. Instead of specifying components within a work system, the focus should be placed on the forces that drive the work towards what we call the unsafe boundaries. So, it’s a very dynamic model. High reliability organizing, so studies of nuclear military applications showed that a mixture of structure and culture create a really melting pot of a great response or a great way to manage these complex, dangerous technologies. They use principles of flexibility and redundancy to create the conditions for success. And lastly, resilience engineering, most recently the most recent development in complex thinking. All these ideas have been combined and integrated. Resilience engineering proposes that our focus should be on understanding the gap between workers imagined and workers done, and the sources and nature of the variability, and also focus on creating success.

So, sense-making is a little tool that is really appropriate for dealing with complex safety problems. Sense-making is a process of understanding. It can be individual or it can be in the collective as a group. It’s a valuable tool. It involves collecting information, analyzing, interpreting, and creating solutions that address the deep and underlying issues more effectively. And some of the activities that you might engage in if you’re looking to do sense-making include asking neutral, humble questions, defining the problem, developing and using models, investigating, simulating and modeling, experimenting and testing, engaging in debate and productive conflict, constructing explanations, and importantly co-creating solutions. So, that diversity of opinion, different views regardless of your expertise or experience, bringing those folks together can sometimes result in unexpected synergies.

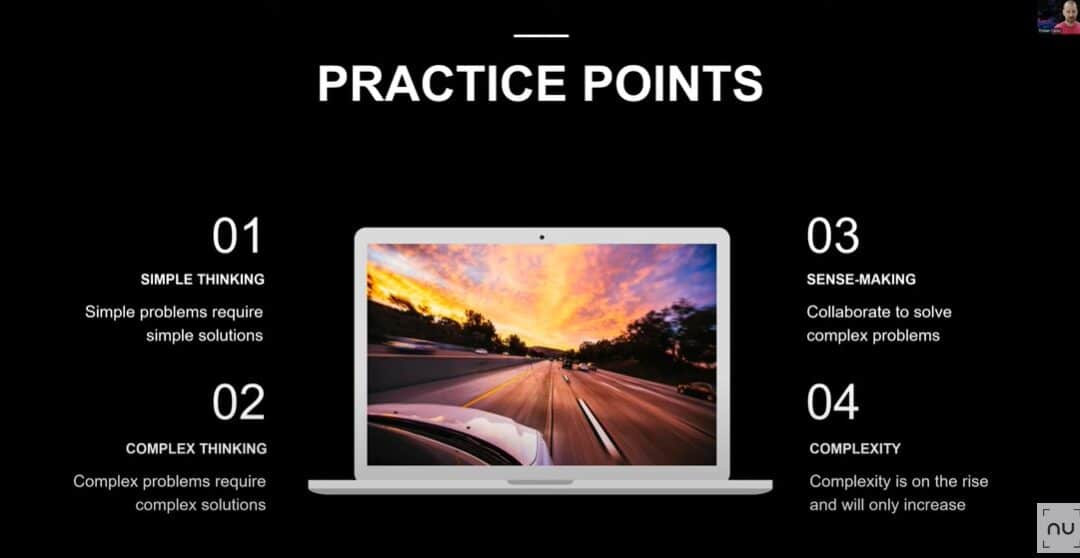

So, that brings us to the end of this little special edition. Simple thinking, simple problems require simple solutions. Complex problems require complex solutions. Is fairly straightforward, isn’t it? But there’s a lot of detail of course to unpack there. Sense-making is a collaboration approach. So, bringing diversity together to solve complex problems. And complexity is not going to go away, it’s just going to increase and become more and more commonplace. So, as that occurs, maybe the applicability of our simple safety models might run out of steam. But that’s all from me. So, thank you so much for your attention during this brief special edition safety science essentials and stay tuned for the next edition, where we’ll start to do a deeper dive into simple safety models. Thank you.